Author: María Merino

The answer is, unequivocally: YES.

To better frame these reflections, we start from the conceptual framework defined by the World Health Organization regarding the so-called social determinants of health (SDH). These are defined as “the circumstances in which people are born, grow, work, live and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life” (1).

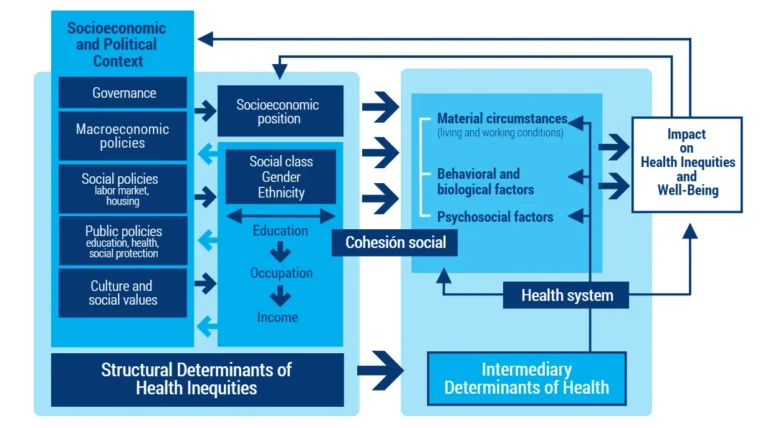

In its conceptual framework, the World Health Organization distinguishes between structural and intermediary social determinants (1) (Figure 1):

- Structural determinants include the socioeconomic and political context in which power and other valuable resources are produced and distributed unequally among different social groups in terms of social class, gender and race/ethnicity. Social inequalities in turn produce inequities in health and wellbeing, understood as unfair and avoidable differences whereby disadvantaged social groups systematically experience worse health outcomes than privileged groups.

- Intermediary determinants are the living and working conditions closest to people’s everyday reality: employment and working conditions, housing, transport, psychosocial conditions, among others. It is important to note that this conceptual framework implies a causal chain in which structural determinants are understood as the causes of the intermediary determinants.

Figure 1. The conceptual framework of the social determinants of health.

Source: Organización Panamericana de la Salud (1).

Applying this theory, we can translate these concepts into the field of immunity. In the current influenza epidemic (2), messages about how to strengthen the immune system abound. In his excellent public engagement work, Dr Alfredo Corell explains that immunity is modulated by sex, age and even time of day, and he highlights habits that support our defences (3) (Figure 2):

- Sleep well (both quantity and quality; keep naps short).

- Do moderate physical activity (avoid a sedentary lifestyle).

- Maintain a healthy diet (avoid ultra-processed foods).

- Reduce stress (and look after emotional health).

- Keep reasonable hygiene (without excess).

- Avoid toxic substances.

- Get vaccinated as a preventive measure.

- Socialise (with friends and family).

Figure 2. Elements that activate immunity.

Source: author’ compilation based on (3).

Although these elements do not replace genetics, immune performance can improve or worsen through our daily habits. However, such habits are shaped by factors that are not primarily individual but social. This is where the SDH come into play, which are essential for understanding health inequalities, and which we defined at the beginning of this article.

Two decades ago, several key strands (still relevant today) were highlighted regarding how the social shapes health (4).

- The social gradient. Lower socioeconomic position is linked to lower life expectancy and a higher burden of disease.

- Stress. Sustained exposure to stressful circumstances harms health and shortens life.

- Early years. Support for families and early development influences health across the life course.

- Social exclusion. Poverty, marginalisation and discrimination damage health.

- Work. Less control and more job stress mean a higher risk of illness.

- Unemployment. Secure employment improves health and wellbeing; unemployment is associated with poorer health and higher mortality.

- Social support. Strong networks and relationships improve health.

- Addiction. Use of alcohol, drugs or tobacco is shaped by the wider social environment, not only individual choices.

- Food. Access to healthy food is also a political and structural issue.

- Transport. Systems that promote walking, cycling and good public transport support health.

As we age, the ability of our immune system to respond effectively to pathogens declines (a phenomenon known as immunosenescence), while the SDH accompany us throughout life. Evidence shows a strong correlation between markers of immunosenescence and multiple social determinants, including racial/ethnic disparities, educational level, socioeconomic status, housing and income (5).

Understanding and mitigating the effects of immunosenescence is crucial for developing interventions that support robust immune responses in the population (5), including the habits noted above (Figure 2). However, this must be accompanied by public policies that address the social and economic determinants of health.

In other words: even if we know what the “Harvard plate” is or that exercise is healthy, the real time needed to buy healthy foods, cook well, be active or rest properly (often constrained by work stress, difficulties in work–life balance and the whirlwind of everyday life) can make it unfeasible. Hence, we need a combination of individual habits and structural change, including policies that make “healthier choices” easier day to day, reinforce immune resilience and reduce health inequalities. Appropriately addressing the social determinants would not only improve immunity but also overall health outcomes (6).

References

1. Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Determinantes sociales de la salud [Internet]. 2025 [citado 4 de diciembre de 2025]. Disponible en: https://www.paho.org/es/temas/determinantes-sociales-salud#marco

2. Instituto de Salud Carlos III. Informe semanal de vigilancia de infecciones respiratorias agudas (SiVIRA). Semana 47, año 2025 [Internet]. Madrid: Instituto de Salud Carlos III; 2025 [citado 4 de diciembre de 2025]. Disponible en: https://docsivira.isciii.es/informe_semanal_SiVIRA_202543.html

3. Entrevista a Alfredo Corell: Inmunidad en forma [Internet]. La aventura del saber. RTVE; 2025 [citado 4 de diciembre de 2025]. Disponible en: https://www.rtve.es/play/videos/la-aventura-del-saber/alfredo-corell-inmunidad-forma/16798405/

4. Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo. Los determinantes sociales de la salud. Los hechos probados [Internet]. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo; 2003 [citado 4 de diciembre de 2025]. Disponible en: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/promocionPrevencion/promoSaludEquidad/equidadYDesigualdad/docs/hechosProbados.pdf

5. Wrona MV, Ghosh R, Coll K, Chun C, Yousefzadeh MJ. Frontiers | The 3 I’s of immunity and aging: immunosenescence, inflammaging, and immune resilience. Frontiers in Aging. 2024;5:1490302.

6. Ruiz Álvarez M, Aginagalde Llorente AH, del Llano Señarís JE. Los determinantes sociales de la salud en España (2010-2021): una revisión exploratoria de la literatura. Revista Española de Salud Pública. 2022;96:e202205041.